Much of the business of financial markets is the business of prediction. But beyond predicting the future, the markets also guide decisions about allocating resources today. Financial conditions tighten or loosen as expectations change. For many market actors, expectations can matter as much as, or even more than, reality.

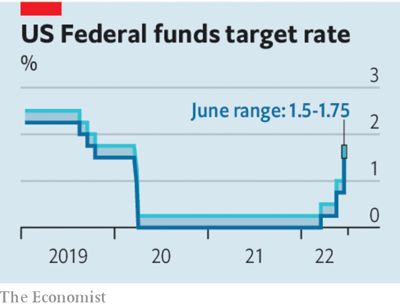

In January investors expected the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates to just 0.75% by the end of the year. Since then, expectations have shifted dramatically: by late June markets were expecting rates to hit 3.5% by the end of 2022. This change in expectations is far bigger than the actual move in interest rates, which have climbed by 1.5 percentage points over the same period. The impact of this duality—that expectations have leapt while reality has only hopped—was plain to see on July 14th, 15th and 18th as America’s six largest banks, Bank of America, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase, Morgan Stanley and Wells Fargo, reported earnings for the second quarter.

The activities of the banks that run on expectations—conducted by the slick investment bankers who advise on major corporate investments, like mergers and acquisitions, and help firms go public or issue debt—had a torrid quarter. Investment-banking revenues (excluding trading) plunged by 41%, year on year, at Goldman, by 61% at JPMorgan and by 55% at Morgan Stanley. Investment bankers who underwrite loans for deals have had a particularly rough time. All banks took losses of varying sizes on their “bridge books”, the portfolios of loans they have yet to sell to investors but have agreed to issue for private-equity deals or mergers. These write-downs added up to more than $1bn in losses across the big banks.

Investment banks’ trading businesses fared better. These are often volatile, and tend to do well during periods of chaos and poorly in times of calm. Markets revenues climbed by 21% on the year at Morgan Stanley and 32% at Goldman, benefiting from bond-market turmoil as investors braced themselves for higher rates.

But it was the usually staid business of retail banking that really boomed. In the early phase of a tightening cycle bankers see the net interest income they earn on things like business and credit-card loans rise, as appetite for them has yet to diminish. Last quarter demand for loans roared, even in the face of modestly higher rates. Swelling loan portfolios and higher rates contributed to a jump in net interest income (nii). Bank of America’s nii rose by 22% on the year, Citi’s by 14%.

Consumer spending on credit cards leapt by 15% on the year at JPMorgan, 18% at Citi and 28% at Wells, driving card balances up. Customers have been “revenge spending” on travel and dining—expenditure in those categories climbed by 34% on the year at JPMorgan—and reducing spending on goods, like apparel and home improvements, which dropped by double digits at Wells. Commercial bankers did well, too. They grew their corporate-loan books by a whopping 7% on the year at JPMorgan. “We have never seen business credit be better, ever, in our lifetimes,” said Jamie Dimon, the boss of JPMorgan, on the firm’s earnings call.

In this environment the central-banking playbook of the 2010s is failing. It was built around low global inflation and designed to dispel the notion that rates might rise. Pivots are rare because policymakers have been unwilling to surprise markets by breaking their “forward guidance”—even the Fed’s decision this week appears to have been leaked two days earlier. Restricting themselves to sequential policy changes, signaled in advance, makes central banks slow on their feet. The result is more volatility in markets and interest rates, not less. As competing goals make the course ahead harder to predict, central banks would do well to stay nimble.

Login

Login